One centimetre of topsoil can take 1,000 years to form.

Soil

Messy, downtrodden, essential. Soil is the basis of most habitats on earth. Each and every woodland is a representation of the soil it grows on, and each handful is bustling with life.

What is soil?

Soil is a mix of organic matter, minerals, water, air and organisms. It holds nutrients and water that plants use to grow, and also holds carbon.

Soil is structured in layers called horizons – the organic layer, topsoil, subsoil and parent material – which sit on top of a mass of unweathered rock called the bedrock. Most soil wildlife lives within the first five centimetres of the soil, which is rich in dead and decaying leaves and other organic matter.

Together, these horizons make up the soil profile, which tells the story of how the soil was formed. Not all soils were created equal, even in woodlands, with two main soil profiles affected by different flora, fauna and geology.

Soil in broadleaf woodland

The upper layers of soils in a broadleaf wood are mainly made up of the previous autumn’s dead leaves and twigs, along with other material that landed there. A few millimetres down you’ll find the fragmented organic remains from previous years, mixed up with old faecal remains from soil invertebrates, such as earthworms, that chew up leaf litter.

Soil in pine woodland

Pinewood soils, on the other hand, are very different. Since conifer trees tend not to drop their needles each year, the underlying soils lack organic matter. In addition, the soils that conifer trees thrive in tend to be much more acidic, which makes them hostile environments for most earthworms. This lack of worms means there isn’t anything to process the decaying matter in the soil, meaning it simply lies there and is broken down very slowly by fungi and soil arthropods.

There can be a layer of decaying pine needles around 10–20cm thick in pinewood soils, and it tends to heave with vast numbers of tiny animals, mainly mites and springtails.

Why is soil important?

The invisible world beneath our feet is often overlooked and undervalued. Yet soil is a vital life support system – for us as well as wildlife.

Carbon storage

It’s thought that soil is the second largest active store of carbon after the oceans, and there is more carbon stored in soil than in the atmosphere and vegetation combined! When soil is damaged, however, it releases that carbon back into the atmosphere, exacerbating climate change rather than helping to stop it. Find out more about woodland carbon.

Biodiversity

Just one teaspoon of soil can support more microbes than there are people on the planet. Together with soil invertebrates, fungal threads and plant roots, they keep the soil healthy and rich in nutrients, which then supports all the life on the surface. From trees to bees and birds, the whole ecosystem is underpinned by soil.

Food production

It’s thought that around 95% of our food is directly or indirectly produced on our soils. Crops rely on a thriving topsoil rich in bacteria, fungi, earthworms, insects and microscopic creatures that, together, help air, water and nutrients move through the soil and feed the plants. Healthy soil can also make crops more resilient to pests and diseases and is less prone to waterlogging and erosion, helping them weather climate change too.

Flood protection

Healthy soil has lots of pores and spaces between its particles which act like a giant sponge, stopping water from running off fields. This lowers the risk of flooding downstream and, on farmland, helps prevent chemicals and fertilisers from being washed into waterways.

Tree health

The wealth of nutrients and minerals in the soil feeds the trees in our woods, as well as supports the ‘wood wide web’. Healthy soils also anchor tree roots in the ground, preventing them from toppling over in high winds.

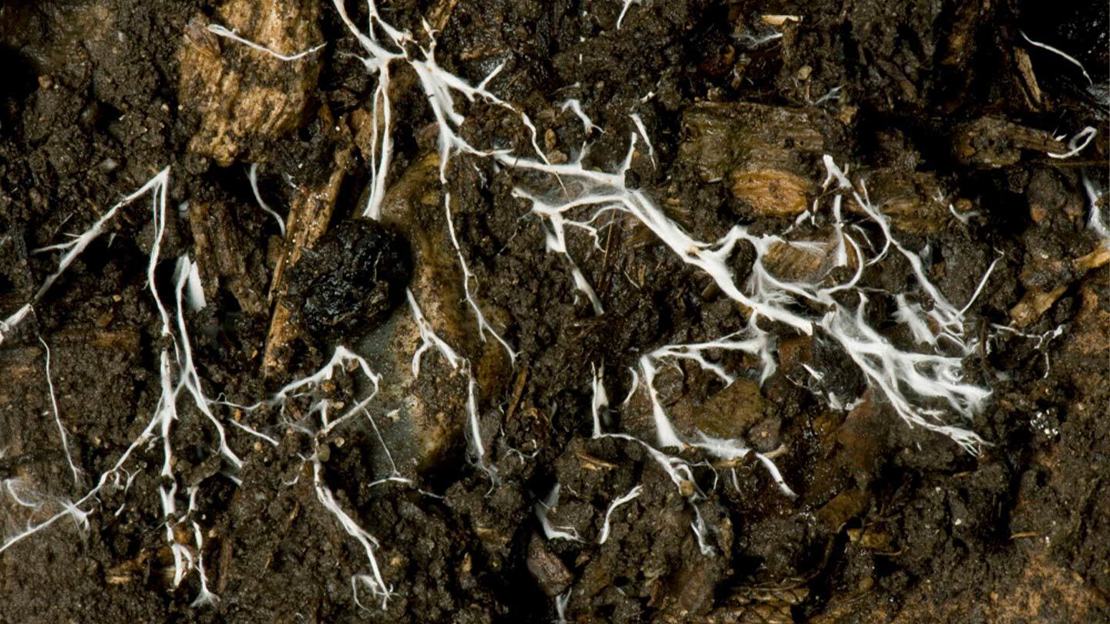

Credit: John Bridges / WTML

Mycorrhizal networks

Also known as the wood wide web, the soil is full of strands of fungus called hyphae. The hyphae connect with the roots of trees and help them take in, and share, resources like water and nutrients in exchange for sugars made during photosynthesis. Mycorrhizal networks are still being studied, and may be used by trees to communicate distress signals which alert nearby plants to raise their defences.

Soil wildlife

Soil is teeming with life: from moles, badgers and other mammals digging out their homes, to soil mites and springtails chomping through the mulch, to bacteria that influence its composition. Plants and fungi rely on soil for somewhere to grow and source their water and nutrients.

Earthworms are perhaps our most familiar soil-dweller, and for good reason. They’re nature’s plough – aerating the soil as they burrow along, improving drainage with their tunnels, recycling organic matter as they eat and converting it into a superpowered soil fertiliser when it comes back out the other end.

Threats to soil

Soil is crucial for all life, yet our soils are under threat from intensive farming, chemicals and pollution, and erosion by wind and rain. One centimetre of topsoil (the fertile layer that plants need to grow) can take 1,000 years to form, but it’s currently estimated that more than two million hectares of topsoil are at risk of erosion in the UK every year. Almost four million hectares are at risk of compaction – and with no pores in the soil structure, water can’t filter through, soil invertebrates can’t survive and plant roots can’t grow properly.

What can be done to protect soil?

Rethinking the way we manage the land is the first step to nurturing healthy soil. Reducing tillage, providing permanent soil cover and using crop rotations can all encourage good soil structure where beneficial invertebrates and fungi can thrive. Reducing the use of chemicals – including pesticides – which can kill the earthworms, springtails and other creatures crucial to healthy soil, will also protect it.

Planting trees can protect soil from erosion and improve its ability to absorb water. They can also help create new layers of topsoil crucial to plant growth by dropping leaves.

Reviving ancient woodland soils

Ancient woods are nothing without their soil. These areas have been constantly wooded since at least 1600 (or 1750 in Scotland) and their soils have lain undisturbed for centuries. They can host a range of rare plant species and associated fungi which in turn attract other ancient woodland specialists.

Even if an ancient woodland is replanted with conifers, as many were in the war effort, its soil can still contain important ground flora, fungi and dormant seeds. By sensitively restoring these planted ancient woods by selectively removing conifer trees, we can move the wood towards a revitalised, more natural state and revive the hidden secrets in the soil.